Water Voles - Healthy Life Essex

Home » Articles » Outdoor Life » Wildlife » Mammals » Water Voles

Water voles in Essex

About the Water vole

The water vole was most famously immortalised in the character of ‘Ratty’ in the 1908 classic children’s story, The Wind in the Willows. At that time water voles were common on every river and stream in Essex but a century on they only occupy 5% of their original territory. Habitat destruction used to be the major cause of extinctions, but now it is predation by non-native North American mink that is responsible formuch of this accelerated decline.

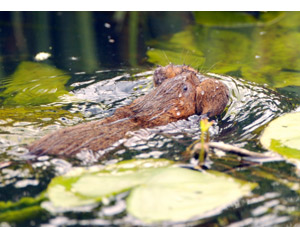

Brown rats and water voles are often mistaken for each other as they are similar sized animals, often  found living in the same habitat. While rats are generally larger than water voles, weighing up to 500g, young rats and adult water voles overlap in size so this cannot be used as a reliable, distinguishing feature. While a rat has a long, hairless, scaly tail, very obvious large ears and the sharp, pointed nose, the water vole’s tail is short and hairy, only half the length of its body, the ears are almost invisible under its fur and the face has a generally more rounded, chubby appearance.

found living in the same habitat. While rats are generally larger than water voles, weighing up to 500g, young rats and adult water voles overlap in size so this cannot be used as a reliable, distinguishing feature. While a rat has a long, hairless, scaly tail, very obvious large ears and the sharp, pointed nose, the water vole’s tail is short and hairy, only half the length of its body, the ears are almost invisible under its fur and the face has a generally more rounded, chubby appearance.

Water voles prefer sites with wide strips of vegetation along the banks or in the water. This provides useful cover from predators, as well as an abundant supply of food throughout the year. They are almost  entirely herbivorous so this lush vegetation is essential. They also thrive in areas which have relatively soft, but stable, banks for their burrows. The preference is for steep, tall banks so that nest chambers can be situated above high water.

entirely herbivorous so this lush vegetation is essential. They also thrive in areas which have relatively soft, but stable, banks for their burrows. The preference is for steep, tall banks so that nest chambers can be situated above high water.

Water voles are not strong swimmers and tend to be very buoyant, especially when young, which makes water courses with strong currents difficult to navigate. They are therefore more likely to be found in slow moving rivers and streams, or water-bodies such as ditches, dykes, ponds and moats. However water voles have been known to colonise the lower freshwater reaches of tidal rivers with quite extreme water level fluctuations. While they will happily populate the brackish waters of coastal borrow dykes, they are rarely found breeding in estuaries or salt marsh except where there are relatively stable, reed fringed lagoons.

Where water channels dry out completely, voles are exposed to increased chance of predation and may either be killed directly, or choose to relocate to more optimal habitat nearby. Rapid depopulation of dry channels is almost always the result. Colonies are also vulnerable to flooding and although adults can escape from rising water, it may be impossible for mothers to remove young to safety if the whole burrow system becomes inundated.

If you would like to help water voles ensure that you leave some nice ‘untidy’ fringes of vegetation around ditches, streams and ponds and report any sightings of mink or water voles to the Essex Wildlife Trust’s Water for Wildlife Officer Darren Tansley – 01621 862995

email: darrent@essexwt.org.uk.

Water Voles In Essex

Essex has seen a dramatic decline in water voles over the past century, and in particular, since the early 1990s. It is estimated that populations have declined by over 90% with rivers such as the Roding and Colne seeing an almost total population crash.

In contrast in the south of the county, the River Mardyke is still well populated along at least 5km around the North Stifford area. The coastal grazing marshes and borrow dyke systems also contain healthy colonies of water voles and contain some nationally important populations. Sites such as Hamford Water, Fingringhoe Ranges, Old Hall Marshes, Tollesbury Wick (a national key site), Bluehouse Farm and the Thames marshes are all still occupied at, or near, 1990 levels. Mink are penetrating into some of these areas, however, and unless monitored and excluded, may have a significant impact on these colonies.

In contrast in the south of the county, the River Mardyke is still well populated along at least 5km around the North Stifford area. The coastal grazing marshes and borrow dyke systems also contain healthy colonies of water voles and contain some nationally important populations. Sites such as Hamford Water, Fingringhoe Ranges, Old Hall Marshes, Tollesbury Wick (a national key site), Bluehouse Farm and the Thames marshes are all still occupied at, or near, 1990 levels. Mink are penetrating into some of these areas, however, and unless monitored and excluded, may have a significant impact on these colonies.

There are projects planned for the River Colne, Blackwater, Chelmer and Brain to restore water voles to their previous range, but only 3.7% of the 2007 water vole survey points on the Blackwater Catchment showed occupation so it will be several years before we will know if this has been successful. The main hope is that small pockets of voles in farmland ditches have survived the ravages of predation by introduced North American mink and will be able to return to the main streams and rivers once these are made safe. There are also plans to create new habitat for water voles displaced by coastal realignment and development pressures.

Darren Tansley BSc (hons) MIEEM

Water for Wildlife Officer – Essex Wildlife Trust

Water for wildlife is a unique partnership of the Wildlife Trusts, working with the water companies, Environment Agency and other key partners to provide a more consistent and targeted approach to wetland conservation across the UK.

Picture Credits

“Water Vole eating grass” by Chris Strachen

“A mother ferries her young water vole to safety” Russell F Spencer

“Water Vole” by Kevin Ritchie